How Binomial is Skeet Shooting?#

Based on Chapter 5 of Think Stats

import os

import urllib.request

import urllib.parse

def download(url):

filename = os.path.basename(urllib.parse.unquote(url))

if not os.path.exists(filename):

urllib.request.urlretrieve(url, filename)

print("Downloaded " + filename)

download("https://github.com/AllenDowney/ThinkStats/raw/v3/nb/thinkstats.py")

try:

import empiricaldist

except ImportError:

!pip install empiricaldist

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from thinkstats import decorate

The Binomial Distribution#

In the sport of skeet shooting, competitors use shotguns to shoot clay disks that are thrown into the air. In international competition, including the Olympics, there are five rounds with 25 targets per round, with additional rounds as needed to determine a winner.

As a model of a skeet-shooting competition, suppose that every participant has the same probability of hitting every target, p.

Of course, this model is a simplification – in reality, it’s likely that some competitors have a higher probability than others, and even for a single competitor, it might vary from one attempt to the next.

But even if it is not realistic, this model make some surprisingly accurate predictions, as we’ll see.

To simulate the model, I’ll use the following function, which takes the number of targets, n, and the probability of hitting each one, p, and returns a sequence of 1s and 0s to indicate hits and misses.

def flip(n, p):

choices = [1, 0]

probs = [p, 1 - p]

return np.random.choice(choices, n, p=probs)

Here’s an example that simulates a round of 25 targets where the probability of hitting each one is 90%.

flip(25, 0.9)

array([1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1,

1, 1, 1])

If we generate a sequence of 1000 attempts, and compute the Pmf of the results, we can confirm that the proportions of 1s and 0s are correct, at least approximately.

from empiricaldist import Pmf

seq = flip(1000, 0.9)

pmf = Pmf.from_seq(seq)

pmf

| probs | |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.116 |

| 1 | 0.884 |

Now we can use flip to simulate a round of skeet shooting and return the number of hits.

def simulate_round(n, p):

seq = flip(n, p)

return seq.sum()

In a large competition, suppose 200 competitors shoot 5 rounds each, all with the same probability of hitting the target, p=0.9.

We can simulate a competition like that by calling simulate_round 1000 times.

n = 25

p = 0.9

results_sim = [simulate_round(n, p) for i in range(1000)]

The average score is close to 22.5, which is the product of n and p.

np.mean(results_sim), n * p

(22.537, 22.5)

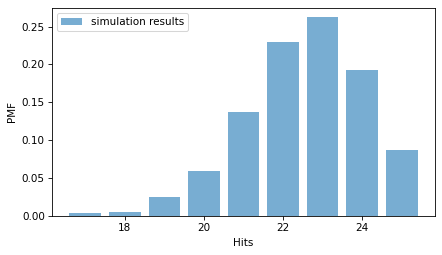

Here’s what the distribution of the results looks like.

from empiricaldist import Pmf

pmf_sim = Pmf.from_seq(results_sim, name="simulation results")

pmf_sim.bar(alpha=0.6)

decorate(xlabel="Hits", ylabel="PMF")

Instead of running a simulation, we could have predicted this distribution. Mathematically, we can show that the distribution of these outcomes follows a binomial distribution, which has a PMF that is easy to compute.

from scipy.special import comb

def binomial_pmf(k, n, p):

"""Compute the binomial PMF.

k (int or array-like): number of successes

n (int): number of trials

p (float): probability of success on a single trial

returns: float or ndarray

"""

return comb(n, k) * (p**k) * ((1 - p) ** (n - k))

This function computes the probability of getting k hits out of n attempts, given p.

If we call this function with a range of k values, we can make a Pmf that represents the distribution of the outcomes.

ks = np.arange(16, n + 1)

ps = binomial_pmf(ks, n, p)

pmf_binom = Pmf(ps, ks, name="binomial model")

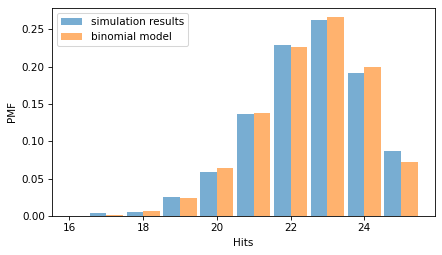

And here’s what it looks like compared to the simulation results.

from thinkstats import two_bar_plots

two_bar_plots(pmf_sim, pmf_binom)

decorate(xlabel="Hits", ylabel="PMF")

They are similar, with small differences because of random variation in the simulation results.

This agreement should not be surprising, because the simulation and the model are based on the same assumptions – particularly the assumption that every attempt has the same probability of success. The real test of a model is how it compares to real data.

From the Wikipedia page for the men’s skeet shooting competition at the 2020 Summer Olympics, we can extract a table that shows the results for the qualification rounds of the competition.

Downloaded from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shooting_at_the_2020_Summer_Olympics_–_Men’s_skeet on July 15, 2024.

filename = "https://github.com/AllenDowney/ThinkStats/raw/v3/data/Shooting_at_the_2020_Summer_Olympics_%E2%80%93_Men's_skeet"

download(filename)

Downloaded Shooting_at_the_2020_Summer_Olympics_–_Men's_skeet

tables = pd.read_html("Shooting_at_the_2020_Summer_Olympics_–_Men's_skeet")

table = tables[6]

table.head()

| Rank | Athlete | Country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total[3] | Shoot-off | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | Éric Delaunay | France | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 124 | +6 | Q, OR |

| 1 | 2 | Tammaro Cassandro | Italy | 24 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 124 | +5 | Q, OR |

| 2 | 3 | Eetu Kallioinen | Finland | 25 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 123 | NaN | Q |

| 3 | 4 | Vincent Hancock | United States | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 22 | 122 | +8 | Q |

| 4 | 5 | Abdullah Al-Rashidi | Kuwait | 25 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 23 | 122 | +7 | Q |

filename = "https://github.com/AllenDowney/ThinkStats/raw/v3/data/Shooting_at_the_2024_Summer_Olympics_%E2%80%93_Men's_skeet"

download(filename)

tables = pd.read_html("Shooting_at_the_2024_Summer_Olympics_–_Men's_skeet")

table = tables[5]

table.head()

| Rank | Athlete | Country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | Shoot-off | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | Conner Prince | United States | 24 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 124 | 12.0 | Q, EQOR |

| 1 | 2 | Tammaro Cassandro | Italy | 25 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 124 | 11.0 | Q, EQOR |

| 2 | 3 | Lee Meng-yuan | Chinese Taipei | 25 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 124 | 7.0 | Q, EQOR |

| 3 | 4 | Vincent Hancock | United States | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 123 | NaN | Q |

| 4 | 5 | Stefan Nilsson | Sweden | 24 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 122 | 6.0 | Q |

The table has one row for each competitors, with one column for each of five rounds.

We’ll select the columns that contain the results and use flatten to put them into a single array.

columns = ["1", "2", "3", "4", "5"]

results = table[columns].values.flatten()

total_shots = 25 * len(results)

total_hits = results.sum()

n, total_shots, total_hits

(25, 3750, 3545)

With 30 competitors, we have results from 150 rounds of 25 shots each, with 3750 hits out of a total of 3575 attempts. So the overall success rate is 95.3%.

p = total_hits / total_shots

p

0.9453333333333334

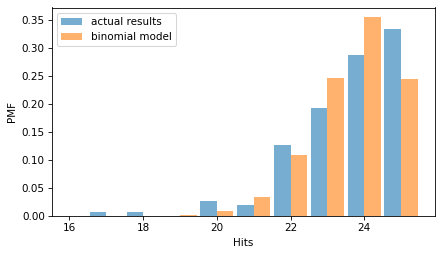

Now we can compute a Pmf that represents the binomial distribution with n=25 and the value of p we just computed.

ps = binomial_pmf(ks, n, p)

pmf_binom = Pmf(ps, ks, name="binomial model")

And we can compare that to the Pmf of the actual results.

pmf_results = Pmf.from_seq(results, name="actual results")

two_bar_plots(pmf_results, pmf_binom)

decorate(xlabel="Hits", ylabel="PMF")

The binomial model is a good fit for the distribution of the data.

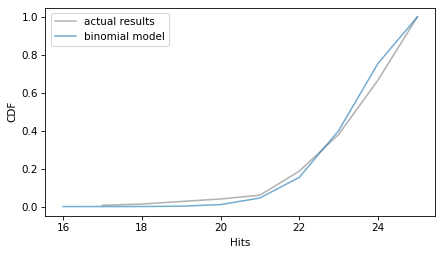

from thinkstats import two_cdf_plots

two_cdf_plots(pmf_results.make_cdf(), pmf_binom.make_cdf())

decorate(xlabel="Hits", ylabel="CDF")